Fritz Horstman, Interacting with Color: A Practical Guide to Josef Albers’s Color Experiments, Yale University Press, 2024.

Interactions with Colors and Materials

Dialogue Between Fritz Horstman and Michael Beggs

Students at Western Connecticut State University experiment with color relativity in one of Horstman’s workshops, Photo by Sabrina Marques, 2023

Fritz Horstman is an artist, educator, author, curator, and musician working in Bethany, Connecticut. Working at a variety of scales, from small drawings to public sculpture, Horstman has created a diverse body of work that transcends traditional disciplinary boundaries. His art frequently seeks to reveal or understand large, slow, tacit natural forces like light and shadow, glacial erosion, or seasonal change. He grapples with these large forces in ways that are closely attuned to and evocative of his artistic materials and processes, creating a charged interplay of subject and object.

This grounding in material and process is partly the result of his long-standing relationship with the work and teaching of Josef and Anni Albers. As Education Director at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Horstman has given many workshops based on the Alberses art and teaching methods to audiences around the world. Horstman also curated the critically acclaimed exhibition Anni Albers: In Thread and On Paper, which appeared in three different guises at the New Britain Museum of American Art, Syracuse University Art Museum, and the Blanton Museum of Art. He is also the author of numerous essays about both Alberses and the recent book Interacting with Color: A Practical Guide to Josef Albers's Color Experiments (Yale Press, 2024).

Fritz and I met in 2010 when I began working at the Albers Foundation, and we were colleagues there for five years. We became good friends, scholarly peers, and frequent artistic and musical collaborators during that time, a relationship that has continued and deepened in the years since I left the Foundation. Our conversation for this dialogue took place in emails over several weeks, and quickly expanded to cover a wide range of our mutual interests. As always among good friends, our conversation ended unfinished, called to an end due to space and time constraints. The result is a snapshot in medias res of our conversation which began and continues off the page.

Michael Beggs

Boulder, Colorado

November 2024

Fritz Horstman, 3 details from Five Feet Under, 2010-11. Nearly everyday for a year, at the same time and location, Horstman positioned a waterproof camera facing upwards on the end of a pole, which he submerged in a pond near his home in Connecticut. The resulting photographs depict the turbidity and changing color of the five feet of water between the camera and the water’s surface, with distorted glimpses of the artist and the landscape behind him. The entire project comprises 180 images, which are installed as a frieze or border around the upper edge of a room.

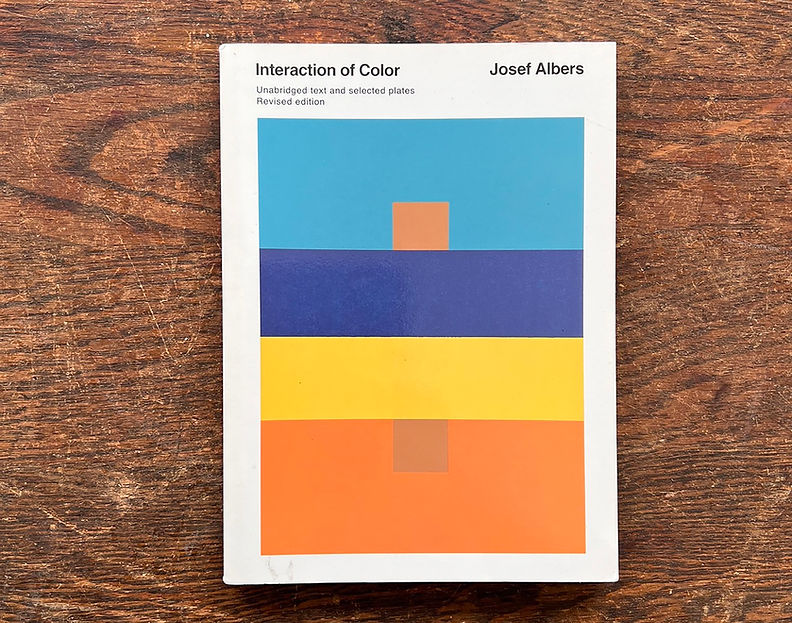

Michael Beggs: Your new book, Interacting with Color: A Practical Guide to Josef Albers's Color Experiments, is a companion book to Albers's seminal 1963 book, Interaction of Color. For those who haven't read Albers's book, can you give us an introduction to Interaction of Color and what it's all about?

Fritz Horstman: Interaction of Color is a summation or crystallization of Josef Albers's approach to teaching color that was developed over 30 years of teaching his color course at Black Mountain College and at Yale University, and was also deeply informed by the learning-by-doing pedagogy that he absorbed as a student and teacher in the 1920s and 30s at the German Bauhaus. At its heart, Interaction of Color is an invitation to look more closely at color, and through that, to be more aware of and articulate about what you're seeing. For the most part there are no rights and wrongs in Albers's approach, no memorization of color systems or rules. Rather, what's most important is being aware of how one perceives certain color phenomena, and to be able to demonstrate that understanding.

MB: I love Albers's description, in his introduction to Interaction, that the book is "a record of an experimental way of studying color and teaching color.” It's a wonderfully open-ended statement of purpose––or invitation, to borrow your phrase––and a prescient one since people can use the book in so many different ways. Your book is subtitled "A Practical Guide to Josef Albers's Color Experiments"––can you describe in what ways the book is a practical guide and why such a guide might be needed?

FH: Albers's book is beautiful and canonical; it has been a vital resource for more than 60 years. However, it is notoriously difficult material, made more so because of the book's layout––text and color images are separated. Though Albers handles it concisely and often poetically, the necessarily abstract discussion of color perception remains, for many, intangible. The original layout of Interaction of Color comprises two separate texts and 150 silkscreen color plates. Subsequent paperback editions have honored that separation. That initial design was dictated in part by the state of the printing technology in 1963, which made it difficult to include high quality images directly alongside text. What was already an abstract discussion of color perception was further complicated by the reader needing to set the text aside in order to see an illustration. I don't mean to take away from the incredible success and achievement of Interaction. It remains a fixture in the firmament of art books for many very good reasons. Even so, for some of the reasons I've listed, as education director at the Albers Foundation, for years I have heard from artists and art teachers who don't quite know how to use it.

I first approached Interaction of Color twenty years ago. Like many others, I found many gems within it, but just as many opportunities to scratch my head in confusion. Shortly thereafter I had the extraordinary fortune to go through the book alongside Fred Horowitz, who had taken Albers's color course at Yale in the 1950s and then taught versions of Albers's material for decades. With Fred, I grasped much of what had been opaque in my initial stab at Interaction. He took me and a group of my Albers Foundation colleagues through three or four exercises, after which I had no problem understanding the rest of the book on my own. My book, Interacting with Color: A Practical Guide to Josef Albers's Color Experiments, aims to provide a similar opportunity to the reader. Selecting what I consider to be the eight most important exercises from Albers's book, I provide many more illustrations of how they may appear in the classroom, of student's solutions to the exercises, and other material that would help someone who wants to get straight into the doing of it. And I was able to include color images directly alongside the text, making the flow of the book that much easier to navigate.

Josef Albers, Interaction of Color, Yale University Press, 1975, Revised Pocket Edition

MB: You bring up a great point that Albers's text can be difficult to grasp for new readers because of both content and design, not to mention the very small number of color examples in the earlier paperback editions. You put it very well in the introduction, where you write that your goal is to “make Interaction of Color accessible to artists, teachers, and learners from all kinds of backgrounds and to hasten the moment when readers are actively experimenting with color."

To do this, you explain and illustrate the process of making and learning from these studies: what materials to use, how to test solutions without cutting up your supply of paper, what a study looks like in progress, what an incomplete or ineffective study looks like, how to discuss them in a class setting, etc. None of these practical concerns are really covered in Interaction, and they really help your readers participate in Interaction of Color, rather than just passively read it.

Of course, the biggest change in the last sixty years is that we now experience a tremendous amount of digitally managed color. I'm curious about how you think Interaction of Color fits into our digital world: Is there any guidance you would give to those wanting to engage with Albers's experiments who work primarily with digital color?

FH: I urge people who are curious about this material to first experiment with colored paper. While it is all very possible to observe on a screen, I think there is something important about searching through swatches of colored paper and holding them in your hands. However, some people prefer learning through digital interfaces or, for whatever reason can't source colored paper.

When Albers said upon arriving to teach at Black Mountain College in 1933 that he was there "to open eyes," he could just as well have said that students would be learning to slow down and be more aware of their surroundings. The question of how and if Albers's color experiments work on a computer screen comes up frequently. To vastly simplify it: Two colors can be juxtaposed just as well in pigment as on a screen. The illusion of color relativity or after-image is just as successful in both contexts.

Your work as an architect is heavily computer-based. Do you find your knowledge of Albers's color experiments informs that work?

MB: Since the majority of design production work now takes place on the computer, if you’re teaching color to current design students, I think you have to include work on the computer. In my last color class, I mixed digital and manual assignments. I knew some of my students would be more comfortable working on the computer, and that it would feel like an anachronistic omission not to work on the computer. But I also emphasized the limitations of digital color, because there are so many colors that we can see that cannot be digitally reproduced.

That color class was composed of graduate students in architecture and landscape architecture, and I tried to develop an Albers-based color class that addressed those disciplines. There are plenty of direct applications when making drawings, but once we begin to think about how color works in the built world, color becomes entangled with material. We can say concrete is grey, but when we look at the Boston City Hall or Yale School of Architecture and we don't say "that's a grey building," we say "that's a concrete building." At some point, material reads as material, and an Albers-influenced approach to color begins to break down.

I know you are also interested in materials and texture, both as an Albers scholar and as an artist. How do you think about color when you are working with other materials? How applicable are the lessons of Interaction of Color to work in three dimensions, or to work with materials whose colors are variable and inherent?

FH: The lessons of Interaction are applicable everywhere. The brilliant progression of that book from color relativity to illusions of transparence and to intervals, is a roadmap for working in any material or mode: everything builds on what came before, and what came before is always present in what comes next. Another aspect of both Anni and Josef Albers's pedagogy that I'm quite interested in is a focus on texture. There's so much to say there, but to draw a throughline, you could compare color relativity to texture relativity. A particular texture––white silk, for example, will visually feel different when juxtaposed with gravel than with porcelain, just as in color relativity green may appear different when surrounded by yellow than it does with blue. This line of thinking shows up more in my own artwork than do many of Albers's other topics. In the sculptures that I call U-Shaped Valleys, for example, I'm not necessarily creating situations of textural relativity, but am very sensitive to the interplay of textural and structural properties of various materials. The structure of folded paper and the shadows it creates has always fascinated me. In working through some of Albers's students' paper folding ideas many years ago, I was suddenly inspired to capture those shadows using cyanotype, the historic photo process that produces blue images. The ongoing body of work that led out of that I call Folded Cyanotypes.

Fritz Horstman, Folded Cyanotype 302, 2024, Cyanotype fluid on paper, 16.5 x 22.5 inches

MB: I've been familiar with your art for a long time now and I hope it's fair to say that some of your recent work is more abstract than the kind of work you were making ten or fifteen years ago. In 2012, say, I think I would have described you as an artist, primarily working in sculpture, whose work seeks to understand or observe the natural world, or perhaps re-presents the natural world in a way that makes the overlooked more visible. But I'm not positive that that would have been an apt description then, and it certainly is not how I would describe your work now. In what ways do you think your work has changed? And can you identify any impulses for those changes?

FH: 2012 is an interesting year for you to choose. Not only had I recently finished my MFA, so I was full of big ideas, and possibly sometimes just full of it, but also you and I were frequently collaborating, both musically and on various activities in the direction of art. None of that is easily teased apart. All of it––our music, drawings, videos, and the other art I was making––I would broadly call both sculpture and drawing. Drawing is an act that makes something visible, and I think of it all very spatially, and therefore sculpturally. In or around 2012 I would have agreed with you that I was re-presenting aspects of the natural world in ways that made a certain poetic sense in an art context. Five Feet Under from 2010-11 is a series of 180 underwater photographs, taken roughly every other day for a year in the same position looking up through five feet of water in the pond near where I live. They are exhibited as a frieze or upper border of the walls all the way around a gallery, showing the wide range of colors of the water through the seasons.

The Folded Cyanotypes and U-Shaped Valleys that I’ve been making for the last decade or so qualify as both drawings and sculptures and are still very related to my interest in natural forms and the human relationship with nature. The development may be that I'm more concerned now with the specific materials I'm using, with understanding how they are altered through various processes, and most of all, with the poetry that can come out of that understanding. For example, choosing two materials that physically push against one another, by which action they inform the viewer about their rigidity, structure, tensile strength, or some other property, is very exciting to me. Both materials may reveal some aspect of their essence and simultaneously make some new meaning together. The shapes and spaces that emerge from the process of making a Folded Cyanotype are equally intoxicating. In both cases, a slipperiness in our perception of materials is revealed. When it is most pronounced, I sense a dissolution of the subject/object dichotomy. That dichotomy often defines our understanding of the relationship between nature and culture, which was quite central to my thinking around 2012. I've been working in both of these series for several years, whereas many of the projects in 2012 were a few months long. To the degree that I'm providing focus that others can perceive to the ideas that I profess here, the extended development period has allowed both projects to become richer and maybe slipperier.

Fritz Horstman, Material with U-Shaped Cuts, 2018, Various materials and ratchet strap, 24 x 24 x 68 inches

MB: I’m interested in this notion of works that blur the line between subject and object––the Folded Cyanotypes which sort of depict themselves. You've got a second new book out of these Folded Cyanotypes––I just got my hands on a copy, it's really lovely––did you have to think about those works differently in the medium of a book?

FH: Although the Folded Cyanotypes reproduce quite well, choosing paper that conveyed some of the texture was important. The matte finish somehow captures that much better than gloss would have. Beyond those sorts of decisions, a book is a different sort of project and is much more collaborative than the process of making the Folded Cyanotypes. I designed the book myself but showed it to and took advice from a number of friends and family members, some of whom are professionals in the world of books, and of course, Lisa Hayes Williams and Vincent Broqua contributed wonderful texts. That sort of collaboration somehow seemed more useful than when I'm making decisions in the studio. It felt more like curatorial work.

MB: It's interesting that you say the book was closer to curatorial work, because it does seem like a mixture between an exhibition catalogue and an artist's book, and I appreciate the slightly more detached tone you've given it by bringing in those collaborators. The texts by Williams and Broqua support your artworks in a beautiful way, and differently to how an artist's statement would have. I've read plenty of artists' books where everything comes from one source, and it can sometimes be too much. The matte paper also works well! I thought the cyanotypes reproduced beautifully and I didn't even really feel a loss of scale in the way I expected. I suppose the largest difference between the book and the actual objects is the physicality of the folds, since looking at the originals you are immediately aware that they have been folded before, and that factors into how viewers perceive them. There's more of a sense of the virtuosity of the folding when you view them in person, and I've heard people marvel at your folding when looking at them. In the book they are a little flatter, a little more purely image––how do you feel about this transformation into two dimensions?

FH: When I frame them, the Folded Cyanotypes are not over-matted. They are float-mounted, so the edge of the paper is visible. A little space is left between the backing board and the glazing so that the dimensionality of the paper isn't squished. The small echoes of the folds that are still discernible are an important part of how they read in person. More than once, someone has stood across the room, and having some understanding of the process, assumed that they were looking at a photo reproduction of the work, not the object itself. When they get closer and see the small shadows and wiggly edge of the paper they realize their confusion. That reveal is a moment I always enjoy watching. As you note, that aspect of the work isn't present in reproduction. Actually, folding each page, or somehow adding dimension––ideas I'm open to, but weren't viable in this production––would close the gap between the actual object and the book, but I'm also interested in keeping that gap open. They are different things and provide slightly different ways of understanding the work.

Fritz Horstman, Folded Cyanotype 276, 2023, Cyanotype fluid on paper, 9 x 12.5 inches

MB: Where can people see more of your work if they want to? And what's coming up for you in 2025?

FH: Fritz Horstman: Valleys and Blue Light is on view at the New Britain Museum of American Art in New Britain, Connecticut until March 30, 2025. I’ll open another solo show at Municipal Bonds in San Francisco, which will run from November 2 through December 21, 2024 called Geometry of Light, which is all new Folded Cyanotypes. On April 10, 2025, another solo exhibition of my Folded Cyanotypes will open at Planthouse Gallery in New York.

Fritz Horstman: Folded Light, co-published by New Britain Museum of American Art, Planthouse Gallery, and Municipal Bonds, 2024

Fritz Horstman is an artist, curator, and educator based in Bethany, Connecticut. His exhibition Valleys and Blue Light is currently on view at the New Britain Museum of American Art. A second solo exhibition, Geometry of Light, is currently on view at Municipal Bonds, his gallery in San Francisco. He is also represented by Planthouse Gallery in New York. Recent residencies include The Arctic Circle Residency and The Bauhaus Residency, with an upcoming residency in northern Michigan at Tusen Takk. He has curated exhibitions across Europe and the US, including Anni Albers: In Thread and On Paper, which was most recently at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas. He is Education Director at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and author of Interacting with Color: A Practical Guide to Josef Albers’s Color Experiments.

Fritz Horstman

.jpg)

Michael Beggs is an architectural designer, artist, and independent scholar. He is the co-author of Weaving at Black Mountain College: Anni Albers, Trude Guermonprez and Their Students (Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, 2023) and has written extensively about Black Mountain College and Josef Albers. He currently resides in Boulder, Colorado.

Michael Beggs