Mark Rothko No. 22 (Untitled)

1961 Oil, acrylic and mixed media on canvas 79-1/2" x 69-1/2”

Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc., 1985

Collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo courtesy The Mark Rothko Foundation

Mark Rothko: Answering the Dark

By Deanna Sirlin

The 33 Orchard St Gallery in New York City currently features an exhibition of anonymous Tantra paintings (through November 5, 2017). These paintings on found paper were made in Rajasthan, India not as works of art but as objects of meditation. The paintings in the exhibition were made from 1970 to 2008 by families that follow tantric Hinduism. Roberta Smith described these tantric works in a 2012 review for the New York Times, “Three horizontal bars, stacked or in a row, represent the three gunas: matter, energy and essence." Of course, this description calls up the work of Mark Rothko, not only in structure but also in the way the artist wanted us to experience the works. I am quite sure that Rothko did not know these Tantra paintings, but the parallels of form and function are uncanny. The tantric works were created for meditation and focus; Rothko made works whose composition and palette were intended to engulf the individual. The idea of an image that is meant for meditation is how I think of my experience of the Rothko Chapel in Houston and of Rothko’s dark palette. Rothko's frequently misunderstood dark paintings led him to a new place in his work, a place that encourages a meditative response from the viewer.

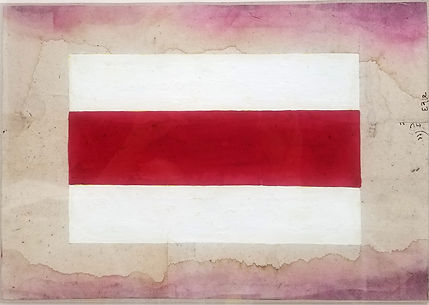

Anonymous,Flow of Life Blood; Udaipur, Rajasthan, 2000, Unspecified paint on found paper, 9¾ x 14 inches (paper), 14 3/4 x 19 inches (frame)

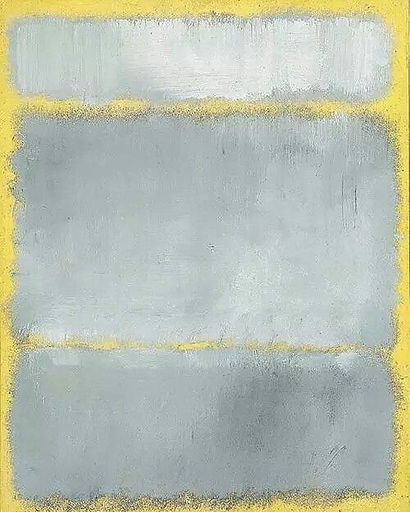

The art critic David Rimanelli recently posted on Facebook a small and beautiful Mark Rothko work in oil paint on paper that had been mounted on canvas, titled "Untitled (Grays in Yellow)” (1960). The work is 23.7 x 18.7 inches. It is an unusual work not only in its color but also in the way Rothko applied the paint, which is active and thick. The edges are not blended but rough. It is a vertical work, with three horizontal bands of grey rectangles of different values on a cool light citron yellow ground. The three grey rectangles have active edges that show an intensity of stroke unusual in Rothko's work. The edges have the texture of dry brushed oil paint that is almost impasto so thick is the paint on top of the ground.

What I found interesting were the comments and responses to this work on Facebook. Almost immediately, there were 148 likes for this post; I am sure that there are even more now. But the comments about the work’s color were very revealing about the viewers’ perceptions. This painting was described in the Facebook comments as bleak, gay, unusual, and the color "wrongly diminishing the true valuation."

How do three greys and a yellow spark so much controversy? Where do all these connotations of color come from? The gallerist John Cheim astutely commented on this post with a quote from the painter Joan Mitchell: "when told by an admiring fan how much they loved her happy yellow paintings Joan replied, ‘What makes you think yellow is happy?’"

This brings me to the reception of The Dark Palette, an exhibition in December of 2016 at Pace Gallery in New York City, in their Chelsea space. It was an eloquent show that got reviews that ranged from the poetic and insightful by John Yau to other critics’ missing the mark entirely.

Mark Rothko

Grays in Yellow, 1960.

23.7 x 18.7 inches

Copyright © 2017 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko

Mark Rothko Black in Deep Red

1957 Oil on canvas 69-3/8" x 53-3/4”

(176.2 cm x 136.5 cm)

Private Collection

© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo courtesy The Mark Rothko Foundation

Mark Rothko Untitled (Rust, Blacks on Plum)

1962 Oil on canvas 60" x 57”

Private Collection, Santa Monica

© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo courtesy The Mark Rothko Foundation

I went to New York to see these Rothko paintings. Rothko’s work is always difficult to reproduce, but the reproductions of this body of work are completely useless. All the nuances of color cannot be seen either on the computer or in the catalogue. This body of work of Rothko's must be experienced in person; the viewer’s eye must allow the time necessary to see the paintings’ hues reveal themselves. In these works, Rothko explores where he could take color to create a space for reflection and revelation.

So many critics and viewers like to see these works as indications of the depression from which the artist suffered. However, I do not think these works are symptoms of depression any more than the darkness of the night sky is depressing. These works were made with an understanding of hue and intensity that has nothing to do with the artist’s ostensibly depressed state or the articulation of depression.

Mark Rothko

Mural, Section 6 {Untitled} [Seagram Mural], 1959

oil on canvas 6' x 15'

Collection of Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko © 1998

Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo courtesy The Mark Rothko Foundation

These dark paintings reflect Rothko’s understanding of color and the path he had been taking beginning with the maroons and alizarins of the Seagram murals (1958) and leading to the paintings he made for the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas commissioned by Dominique and John de Menil in 1964. Rothko made the paintings shown at Pace between 1959 and 1969. Many were first painted on paper and then mounted on canvas. Rothko used acrylic paint in these works, which was in its earliest incarnation. Liquitex produced commercially available, water-soluble acrylic paint in the 1950’s, and paints with high viscosity were available in the 1960s. However, the quality of the color of these paints was nowhere near what it is today. Even in the 1970s and 1980s, acrylic colors were shriller than oil colors, and they had a look of plastic rather than the transparency and luminosity of oil based paints that had been around for centuries. Rothko’s use of this new paint is remarkable: he layered the colors in thin washes so that he was able to create depth through saturation.

Rothko Chapel, Houston,Texas. Photo by Runaway Productions.

I like to imagine the conversations about color Rothko must have had with his close friend, the painter Ad Reinhart, who made hard edge geometric works that reveal their color slowly and was known for his black paintings. In some ways, these two artists were polar opposites, yet their work equally shows their understanding of color and their ability to create nuance in darkness and monochrome. I can imagine that they must have appreciated each other, while also engaging in a competition that lead teach to articulate through paint and color/darkness a new and significant way of working.

It is no coincidence that Rothko’s palette shifted during the upheavals of the 1960s. During the last decade of his life, Rothko lived through the Vietnam war, the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, our lakes and rivers on fire from pollution, and bombings in churches and synagogues. And his palette became darker: reds and maroons, dark blues and greens that are almost black. I am sure Rothko understood the need for this palette during turbulent times, both for himself and the viewer. Rothko wanted to answer the need for a meditation and reflection through color and form. I am not saying that Rothko was trying to express the turbulence of the times through his palette. He was not in the least a narrative artist and I think he would cringe at the notion of seeing these works as biographical. Rather, I think the greatly empathetic nature of this artist lead him to make works that would allow the viewer to reach a different level divorced from the ruptures of life, and through the experience of the work arrive at a meditative and transformative state. This is also what made them perfect for the De Menils to commission Rothko for their nondenominational chapel as a place for all to find quietude and reflection in the palette of darkness.

This year also has been turbulent, not only because of devastating hurricanes, flooding and earthquakes, but also because of political and social upheaval. I and many of my friends and contemporaries feel an unrest reminiscent of our childhood in the 1960s when war and civil unrest in this country played out nightly on our TV screens. It has been a difficult time since the 2016 election, and many, including myself, have had sleepless nights and our minds are deeply troubled. When I saw the dark palette paintings this past December, I felt a quieting of my mind, a focus on their color and scale. A quiet meditative composure filled me, and I noticed that my breathing changed. In these difficult times, I think we need these Rothko works more and more.

Rothko: Dark Palette was at Pace Gallery in New York City from November 4, 2016 – January 7, 2017.

Anonymous Tantra Paintings is on view at 33 Orchard Gallery New York City from September 7 – November 5, 2017.

Deanna Sirlin is an artist and writer. www.deannasirlin.com